Restoring The Glory

of The 1971 National

Champion Howard Bison

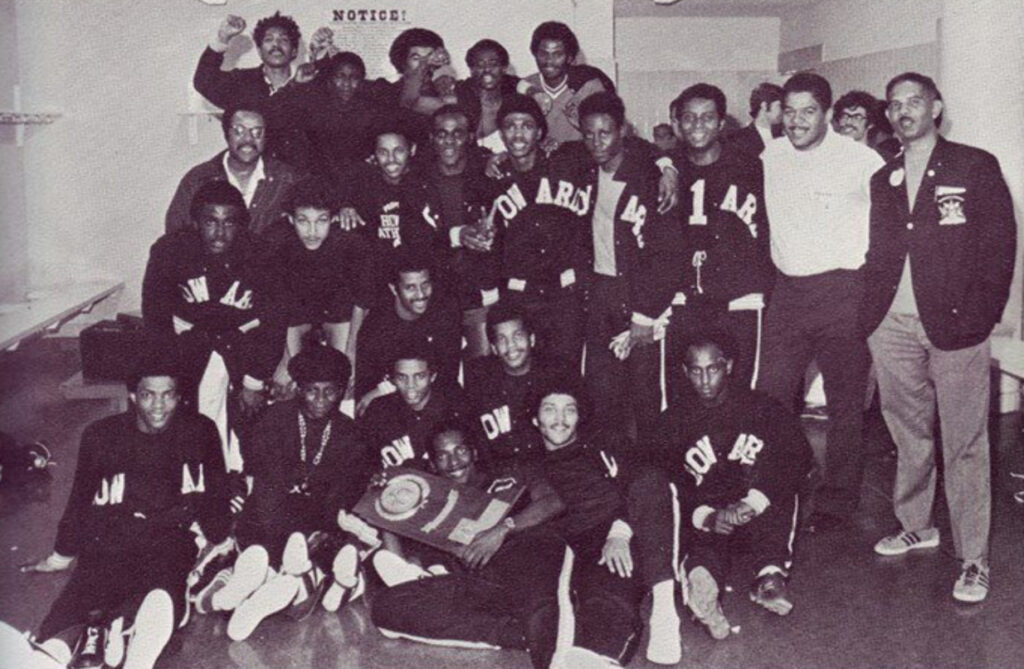

Washington, D.C.-based Howard University had just three weeks to celebrate its 1971 national soccer championship before all hell broke loose. The school would soon learn that it had made history — as the first national champion in the modern era to have its title revoked by the NCAA. The Bison Project, a three-episode podcast, tells the story of Howard’s lost, and in some circles, forgotten championship. Part of an ambitious multiplatform storytelling series called Sports Explains the World, The Bison Project finally answers questions players and fans have had for more than 50 years.

Coach Lincoln Phillips and the 1971 Howard University soccer team always felt targeted. Targeted by opposing players. Singled out by referees. Taunted by racist fans threatened by their mere existence.

Twenty-one days after the team’s historic victory over two-time defending champion Saint Louis University on Dec. 30, 1971, the NCAA received an anonymous note suggesting that Howard had cheated its way to the title by knowingly using ineligible players. As rumors swirled around them, Howard’s players were hardly surprised. After all, how dare this all-Black team, from an HBCU (historically Black college and university), have the audacity to dominate in this all-white collegiate landscape without asking permission?

More than 50 years have come and gone (and eight members from that team have passed away), yet questions remain.

* Was Howard targeted by the NCAA?

* Did the NCAA find a loophole to make an example of the Bison?

* Was Howard’s victory a threat to the system?

Ask any of the men who suited up for Coach Phillips on that fateful day in Miami, and they’ll tell you that they fought and clawed and won the national championship fair and square.

Allegations be damned.

Asterisks be damned.

The NCAA … be damned.

The Bison Project gives these players the long-awaited opportunity to speak their truth; many of them shared their experiences exclusively for this podcast. They all want to see their historic championship returned to its rightful owner, and the testimonies in this series make the strongest case, to date.

Listen to “The Bison Project” series pilot

TEAM Voices

Ian Bain

Country: Trinidad & Tobago

Position: Midfielder

Years: ’71, ’72, ’73, ’74

A freshman on the 1971 national championship-winning team, Ian Bain spent two years abroad (in Spain and England) before enrolling at Howard. Known for his fitness, dribbling and passing, Bain – who captained the 1974 national championship team – is one of three players to have played on both title-winning teams. Teammates called him “Zito,” after the Brazilian great who played on two World Cup-winning sides.

Ian Bain

If the freshman hadn’t already made a name for himself during the 1971 regular season — with his ability to dribble past defenders and run tirelessly for 90-plus minutes — his point-blank finish that secured Howard’s 1-0 victory over Harvard in the NCAA tournament semifinals game most certainly did.

When Bain, who was inducted into Howard University’s Athletic Hall of Fame class of 1997, thinks about the significance of the NCAA’s investigation, it goes beyond the 1971 season for him. “Howard was showing signs of becoming a dynasty, which made the higher rung of the NCAA nervous,” explained Bain, who was one of a team-high eight players from Trinidad & Tobago on Lincoln Phillips’ high-scoring 1971 roster.

“I wonder sometimes if the NCAA didn’t make a choice that would ruin our possibilities over a period of time,” said Bain, a four-year starter who scored 12 goals his freshman year. “It wasn’t just about taking away one championship — I asked myself at some level [if] there wasn’t some kind of sinister, long-term plot to deny us the chance to compete and potentially go on a run of three or four championships, not unlike what Saint Louis did.”

Bain, a retired educator and coach, continued: “I know it hurt my college career. And I know other guys feel the same way — even after 50-some odd years.”

The late soccer journalist Grant Wahl had profiled Bain for Sports Illustrated in 1997. “This was my [first] story for Sports Illustrated, and it came out of a research paper I did for an African American Sports History class with Professor Jeffrey Sammons [at NYU],” Wahl tweeted in June of 2020. “So many good memories from interviewing legendary coach Lincoln Phillips, captain Ian Bain and others from those teams.”

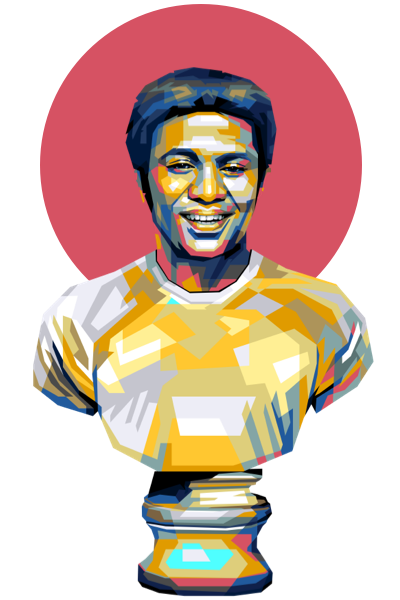

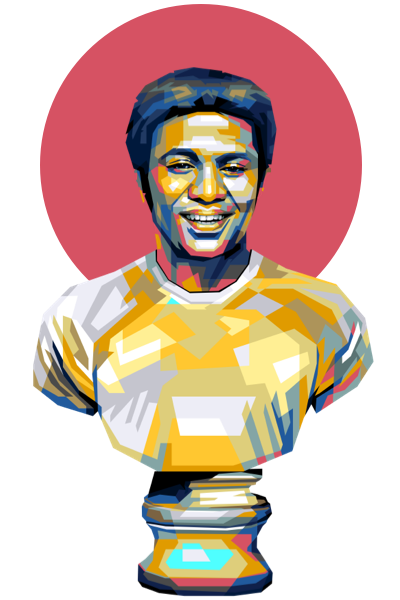

Alvin Henderson

Country: Trinidad & Tobago

Position: Forward

Years: ’70, ’71, ’72

An All-American — and Dean’s List student — Alvin Henderson stood a generous 5-foot-8 and was known for his timely runs and uncanny ability to score goals with his head and finish with both feet. He scored the winning goal in the 1971 final — a rocket from 25 yards out (assisted by teammate Stan Smith).

Alvin Henderson

When the idea of The Bison Project was presented to Henderson with the goal of restoring the glory — and trophy — of the 1971 championship to Howard, he agreed to tell his story under one condition: that the recount appropriately acknowledge the squad from the prior season.

“That 1970 team that reached the semifinals of the NCAA tournament laid the foundation for everyone, including for Lincoln Phillips, who was a young coach at the time,” he explains. Henderson was a freshman forward (scoring 21 goals) on that ’70 team and a sophomore (21 goals) on the ’71 squad that featured one of the fiercest front fours — complemented by midfielders Mori Diane and Ian Bain, and fellow forward and sophomore Keith Aqui — in the history of college soccer.

Born in the city of Newcastle in northeast England, Henderson, whose mother was from Wales and whose Trinidadian father studied dentistry in Durham before becoming a FIFA referee — has been an integral voice and consultant on the Bison Project.

The retired physician holds firm that the NCAA first took notice of Howard with the seemingly sudden emergence of fellow Trinidadian Aqui, who walked onto the team in 1970 as a 25-year-old relative unknown. “Over the course of that 1970 season, Keith became the best player on our team, bar none,” says Henderson of Aqui, who scored 25 goals his first year. “That, to me, was the beginning of the NCAA’s putting Howard on their radar.”

Adds Henderson (whose teammates call him “Hendo”): “I look at the roster from ’71, and it really was a dream team for what we know — with our back four of Steve Waldron, Desmond Alfred, Tony Martin and Rick Yallery-Arthur; midfielders Stan Smith and Donnie Simmons; and the four lethal horsemen, including me, Ian, Mori and Keith; and a strong core of reserves. There was no stopping us.”

That’s hardly hyperbole. Howard’s 1971 team finished the season with a perfect 15–0 record.

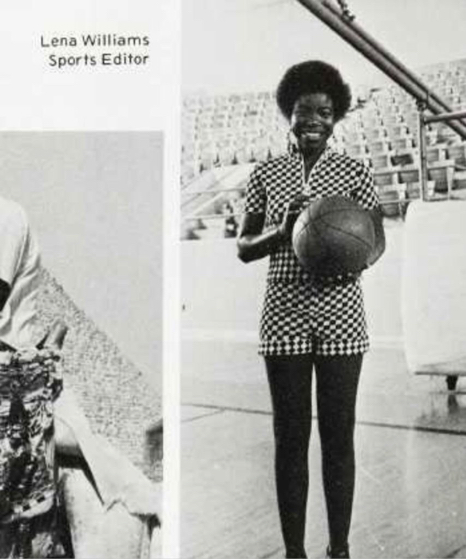

Lena Williams

Country: USA

Position: Student & Journalist

Years: ’68, ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72

Lena Williams first fell in love with “the beautiful game” in early 1970, when her budding reporter’s instincts drew her to Howard’s men’s soccer team. A student-reporter for the university’s newspaper, The Hilltop, at the time, Williams endeared the team of immigrants to the majority African American student body, which knew little about soccer and for whom American football and basketball were king.

Lena Williams

A native of Washington, D.C., Williams became enamored with soccer in early 1970, when her reporter’s instincts drew her to Howard’s men’s soccer team. A reporter for Howard’s newspaper, The Hilltop, at the time — with aspirations to become its first female sports editor — Williams’ profiles of players endeared the team of immigrants to the majority African American student body, who knew little about the sport.

“I knew I had to learn the game — the rules and the nuances — to properly tell their stories,” explained Williams, who went on to become an intern-reporter for The Washington Post on her way to an award-winning journalism career that included more than three decades at The New York Times. “During that ’71 season, as the wins piled up for Howard, it was clear this team was on the cusp of something special.”

Williams had graduated by the time the NCAA started its inquiry of Howard. She remembers how angry she felt. “When you think about it, the NCAA had accused us of cheating, and that’s something in sports that you just never get over,” she explained. “If you are labeled a cheat in sports, the allegation alone could destroy your career and kill legacies. When I got to Howard in September of 1968, we were quick to react to anything and everything that felt like injustice.

“But by the early ’70s — after the death of Martin Luther King and the hot summer of 1967, when riots erupted in several northern cities, including D.C. — things were changing. We were getting out of Vietnam, neighborhoods had begun to integrate, and with the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act, our sense of urgency had begun to wane.”

Williams is the author of It’s The Little Things: The Everyday Interactions That Get Under The Skin of Whites and Blacks, which was published by Harcourt in 2000.

Lending her voice to the Bison Project, for Williams, is unfinished business — an opportunity for her, too, to speak her truth.

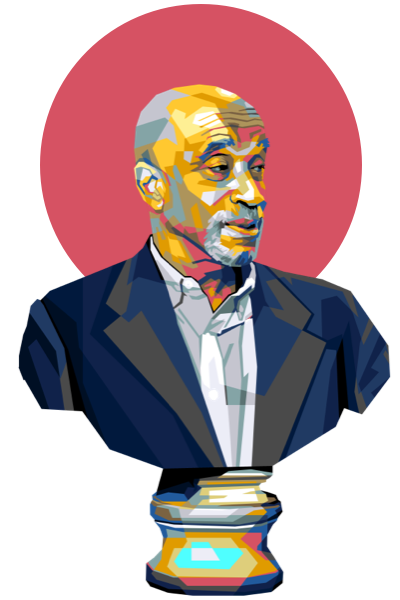

Ted Chambers

Country: USA

Position: Coach & Athletics Director

Years: ’45-’75

There is no Howard soccer story without James T. “Ted” Chambers, who joined the Bison coaching staff in 1945 after serving in the Army in World War II. In addition to soccer, Chambers coached swimming, basketball, track, boxing, wrestling, cricket and football, and taught physical education.

Ted Chambers

There is no Howard soccer story without mention of Chambers, who joined the Bison coaching staff in 1945 after serving in the Army during World War II. Chambers was an influencer even beyond Howard, and helped launch the D.C. Collegiate Soccer Association in 1958 and served as its president for six years.

Born in Union, West Virginia, Chambers established Howard’s soccer program, and had an impressive record (104-27-11) as coach. His 1961 Bison team won the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) championship with a 3-2 victory against Newark College of Engineering. That ’61 Bison squad was led by two Bermudians (Alex Romeo and Cecil Durham) who were inducted into Howard’s Athletic Hall of Fame in 2014.

Chambers also coached swimming, basketball, track, boxing, wrestling, cricket and football, and taught physical education at Howard. He also served briefly as the school’s director of athletics, before retiring in 1975.

He passed away in 1992, at age 91.

Amdemichael Selassie

Country: Eritrea

Position: Goalkeeper

Years: ’71, ’72, ’73, ’74

A strong and silent player, Amdemichael Selassie was a complete goalkeeper, known to dive only when necessary. After the team won its 1971 championship – and later visited Jamaica – Selassie’s name drew thunderous applause from the Jamaica National Stadium crowd (which wrongly assumed Selassie was related to Emperor Haile Selassie, whom Rastafarians proclaimed as their living god).

Amdemichael Selassie

A strong and silent player who could play in goal and at forward, Selassie was known to dive only when necessary.

In the championship game in 1974, Selassie – by now, a senior – was to have gotten the start, but Lincoln Phillips famously gave the nod to freshman Trevor Leiba, who alternated games with Selassie during the regular season and had started the 2-1 semifinal win against Hartwick College.

Selassie clearly wasn’t happy with the benching.

When approached by Selassie’s wife at the team’s 25th anniversary reunion in 1999, Phillips assumed the goalkeeper might still be perplexed at being left out of the pivotal title match. Wrote Phillips in his 2014 autobiography Rising Above the Crossbar: The Life Story of Lincoln “Tiger” Phillips, “Mrs. Selassie, a quiet lady, approached me and said: ‘Thank you for my husband.’ ”

At first, Phillips was confused at her comment, but recalls Mrs. Selassie’s explanation: “When the couple faced problems, her husband often mentioned the ways in which we had overcome obstacles at Howard,” wrote Phillips, who said of the exchange, “It was the best tribute I could have hoped for.”

In the weeks leading up to the team member interviews for The Bison Project, conducted in-person at Howard’s Law School, an ailing Selassie declined the invitation to attend: “Due to my current health situation, I don’t have the energy to converse, even for a minute via phone. Whatever you want to accomplish I wish you success,” he texted via WhatsApp to storyteller Mark W. Wright. “And my teammates can fill [in] for me, because we succeeded in our goal together to be champions. Thanks for thinking about me during my difficult conditions.”

Twenty-three days later – on Feb. 7, 2022 – Selassie passed away. He was laid to rest in his native Eritrea, with full honors by the government.

Alvin Henderson remembers Selassie as a great person whose talents were understated. “During the summers, Amde would play for the Haitian [club] team in D.C. as a forward and was outstanding,” he said. “In 1973, I’m sure if he had played forward he would have made the starting 11. He was that good.”

Steve Waldron

Country: Trinidad & Tobago

Position: Defender

Years: ’71, ’72

Even before making his way to America – and joining Howard’s soccer team in 1971 – Steve Waldron, alongside his future Bison teammates Ian Bain and Alvin Henderson, had helped guide St. Mary’s College to the intercollegiate soccer championships in 1968 in their native Trinidad & Tobago. With the Bison, Waldron was the starting right back who also had experience playing in central defense. He was a quick and hard tackler who often ventured forward to provide critical crosses for attacking players.

Steve Waldron

When Waldron arrived at the Hilton Hotel off of Military Road in Washington, D.C., to meet up with his former Bison teammates to be interviewed for The Bison Project, he had a bit more baggage than the rest. While some teammates brought old press clippings and magazine features from their glory days, Waldron’s 24-by-36-inch framed poster – a gift from his wife for his 70th birthday – stole the show.

“This is the 1971 team – all the guys,” he said, pointing to each player. “We had just arrived in Jamaica and met [future Prime Minister] Michael Manley after we beat Saint Louis in the championship.”

The weight of the frame was hardly a burden for Waldron; he was all too happy to relive the moment with his guys.

Even before making his way to America – and joining Howard’s soccer team in 1971 – Waldron, alongside his future Bison teammates Ian Bain and Alvin Henderson, had helped to guide St. Mary’s College to the intercollegiate soccer championships in 1968 in their native Trinidad & Tobago.

With the Bison, Waldron was the starting right back who also had experience playing in central defense. Waldron, who played two seasons for Howard, was a quick and a hard tackler who often ventured forward to provide critical crosses for attacking players.

None of the memories – so many memories – are lost on him. And he’s got the framed picture to show for it.

Isaac “Ike” Darden

Country: USA

Position: Athletics Faculty

Years: ’68 to Present

Isaac “Ike” Darden has been the keeper of all things Howard athletics since 1968. Darden still oversees the school’s athletic history — from yearbooks and photos to game-day programs and newspaper clippings — from an office in Howard University’s Burr Gymnasium, which opened in 1963. Known for his hand-written letters, cards and phone calls, Darden remains the backbone of Howard sports as the manager of athletic facilities.

Isaac “Ike” Darden

Darden has been the keeper of all things Howard athletics since 1968. He oversees the school’s athletic history — from yearbooks and photos to game-day programs and newspaper clippings — from an office in Howard University’s Burr Gymnasium, which opened in 1963.

A longtime clock operator for all team sports at Howard, Darden fell in love with soccer, a game that was foreign to most African Americans. “I was enthused to be around those guys,” explained Darden, who still holds the keys to the building as manager of athletic facilities. “I was impressed by them — their brotherhood and the atmosphere that they brought to campus,” he said.

Asked to name the best all-around Howard athlete he’s ever seen — in any sport — Darden, 81, does not hesitate: “No question about it, it’s Keith ‘Bronco’ Aqui, and I have seen ’em all.”

Facts.

Eddie Holder

Country: Trinidad & Tobago

Position: Defender

Years: ’70, ’71, ’72, ’73, ’74

While the modern game now puts a lot more emphasis on center backs being comfortable on the ball and starting play from the back, the stopper position is all about defending and doing everything possible to stop a goal from being scored. Played between the fullbacks and midfielders, the player’s main task is to stop attacks up the center. Meet Eddie Holder.

Eddie Holder

Holder played amateur soccer in Trinidad & Tobago before migrating to the States. A reliable and trusted occasional starter for Lincoln Phillips in defense, Holder started in the semifinal (against Harvard) and final (Saint Louis) in 1971 in place of an injured Desmond Alfred, holding his own in both games.

Gerald “Jerry” Grimes

Country: Trinidad & Tobago

Position: Game Announcer

Years: ’67, ’68, ’69, ’70, ’72

Tuskegee University, not Howard, was the school at the top of Gerald Grimes’ list, because “I wanted to fly,” he explained. But a family member who was from Alabama told the young Grimes that he’d never make it in Alabama as a Black man — and an immigrant at that. So, Grimes ended up at Howard, which was his third choice (after Penn State), enrolling in 1967 at age 19.

Gerald “Jerry” Grimes

Making note of his energetic style, Coach Lincoln Phillips encouraged Grimes (friends call him Jerry and Grimes) to use his gift of gab as the team’s game-day announcer and hype man, where Grimes excelled — infusing R&B music of the day to intro the players, to the delight of the “Dust Bowl” crowd.

When asked to explain why the pain of the ’71 championship still stings, an emotional Grimes said: “We know that other schools, like San Francisco, were blatantly cheating. And nobody ever said anything about that. It hurts. At 71 [years of age], it hurts.”

Michael Billy Jones

Country: Sierra Leone

Position: Goalkeeper

Years: ’68, ’69, ’70

A steady goalkeeper who started in 1969 and split time in net for most of the 1970 season, Michael Billy Jones‘ Howard resume might have been highlighted by a 1969 matchup against Davis Elkins University. Billy Jones was the Bison’s lone bright spot — making 16 saves — in the 3-1 loss.

Michael Billy Jones

Ask Lincoln Phillips about Billy Jones, and the one-time goalkeeper will undoubtedly tell the story of the anxiety he felt when he knew it was time to pull Billy Jones, who by season’s end had dropped to third in the rotation (behind Peter Keiller and Gboyega Adelaja, a young upstart Nigerian) from a critical game in 1970, Phillips’ first as head coach.

It happened against UCLA in a semifinal matchup — with Howard clinging to a 3-2 lead, with 15 minutes to go. Billy Jones, then a senior, had looked shaky — his play that day highlighted by a ball he let slip through his legs and into the net.

Predictably, UCLA would storm back to win the game 4-3, ending Howard’s season at 12-1-1. That UCLA would lose in the final, 1-0, to Saint Louis University, was no consolation to the upstart Bison.

Phillips would later write in his autobiography: “I realized I had to pull my keeper, but I was paralyzed by thoughts of his seniority.”

Donnie Simmons

Country: Bermuda

Position: Midfielder

Years: ’70, ’71, ’72, ’73

A technically gifted player with good dribbling skills and passing ability in tight situations, Donnie Simmons kept good distribution balance and worked hard to keep the four front runners (Keith Aqui, Ian Bain, Mori Diane and Alvin Henderson) well fed. Simmons’ cousin was Stan Smith, a three-year captain (in ’70, ’71 and ’72) for the Bison.

Donnie Simmons

As one of four Bermudians inducted into Howard’s Athletic Hall of Fame, Simmons recalls fondly the energy of home games, which featured an attractive brand of soccer that became “must-see events” on campus, with professors often scheduling classes around matches.

“Back then [soccer] was not high-profile in America — everything was [about] American football or basketball,” Simmons said. “But we took it to another level, and once we started to do well, we basically galvanized the entire institution to the extent that people took off classes to come and watch us play.”

Ernest Skinner

Country: Trinidad & Tobago

Position: Team Manager

Years: ’67, ’68, ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72

Upon arriving at Howard University in September 1967 at age 24, Ernest Skinner had no idea what a college major or minor were, and when pressed to declare one, he opted for Accounting and Economics, respectively.

Ernest Skinner

That bit of indecision would work out well for Skinner, who was the manager on Howard’s soccer teams from 1969 to ’72. Skinner earned degrees in Economics and Accounting, and later received a master’s from Columbia in Corporate and Industrial Relations, enjoying a lengthy career in the financial industry.

But soccer is hardly a footnote to his story. Skinner, an avid photographer, co-signs with Alvin Henderson’s stance that Howard’s 1970 team laid the groundwork for future success. He explained, “That 1970 team, coming of age at that critical time in America, set in motion a foundation that changed soccer in America, not just at Howard.”

Tony Martin

Country: Trinidad & Tobago

Position: Defender

Years: ’71, ’72, ’73, ’74, ’75

While he played mostly in central defense, Tony Martin was versatile enough to play across the back and as a midfielder, when needed. He had the range to close down any ball carrier and scored many vital goals from free kicks and corners. Along with Ian Bain and Amdemichael Selassie, Martin is one of three players to have played on both national championship-winning teams.

Tony Martin

Even as a first-semester freshman in 1971, Martin had a knack for communicating with his teammates — even the vets. After all, as a center halfback, “you see the whole operation,” said Martin, who was 23 when he joined the team. “I see what everybody’s doing and what they’re not doing.”

In one particular game, he noticed that Keith Aqui, who was at least two years his senior and the unquestioned star, was going through the motions. “We were playing a team in Newark, New Jersey,” Martin recalls. “And this team wasn’t good. But we were sleepwalking — we had no energy at all. It was 1-1 with 20 minutes to go in the game, and I called out to Keith and said, ‘Keith — we need to get something going. Please — get something.’ He listened to me, and three minutes later, he start to run … we called him ‘Bronco’ because he run like a horse. And he was dancin’ and movin’ and dancin’ and movin’, and about three minutes later, he scored, and we won the game 2-1.”

Unlike many of his teammates who’d been recruited by Coach Lincoln Phillips, Martin — though he went same high school, Queen’s Royal College in Trinidad, as his coach — was not recruited to play at Howard. Rather he was recommended by another QRC alum, Victor Gamaldo, who had played semi-pro soccer with Phillips.

When Martin joined the Bison, he learned the story of the 1970 team losing in the quarterfinals. But he said he noticed that this super-talented team lacked maturity and soccer intelligence. He felt that he, along with fellow freshmen Ian Bain and goalkeeper Amdemichael Selassie, had that in their respective bags to complement the veteran group.

Martin holds firm that Howard was targeted by the NCAA, but added that it was important for him personally to move on and not dwell on the past. “You have to understand,” he explained. “When a chapter is finished, you have to turn the page and keep going. And that’s how I’ve lived life. But I know in my heart we won clean.”

Stan Smith

Country: Bermuda

Position: Midfielder

Years: ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72

A three-year captain (’70, ’71 and ’72), Smith was a steady and smart leader who was the midfield organizer and a good distributor of the ball. He also scored a number of important penalties and anchored the midfield alongside his cousin Donnie Simmons.

Stan Smith

Smith, who played professionally with the Baltimore Comets and San Diego Jaws in the former North American Soccer League (NASL), was important to the Bison team in many ways — including, notably, off the pitch, as he was one of a few players with a car.

Smith and Simmons are two of four Bermudians in Howard’s Athletic Hall of Fame — all four enshrined in 2014. The other two, Dr. Alex Romeo and Cecil Durham were members of Howard’s 1961 Ted Chambers-coached team that won the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) championship.

Said Smith after the team was stripped of the title in ’71: “It was very disturbing once we were stripped, but we held our heads high. We still felt like we were the champions and were treated that way.”

Mori Diane

Country: Guinea

Position: Forward

Years: ’71, ’72

Lincoln Phillips discovered the struggling Embassy Row hotel busboy while he played pickup ball in D.C., and offered him a scholarship on the spot. A star left-winger, the French-speaking Mori Diane had few equals at ball manipulation, former teammate Ian Bain said.

Mori Diane

Ask any of his former teammates, and they’ll tell you that Diane had the ability to unbalance a defense – not only with his speed, but with his jukes and feints, which created scoring opportunities for others. Diane scored the equalizing goal in the 1971 final against Saint Louis University, which set the stage for Alvin Henderson’s game-winner.

Diane acknowledges that the talent on the ’71 team was unmatched, but it was the sense of brotherhood, he said, that made them champions. “One of the biggest strengths of that team was the off-the-field connection that everyone had — the brotherhood,” explained Diane, who left Howard after the ’73 season and had a short professional playing career with the San Antonio Thunder and the Washington Diplomats in the North American Soccer League (NASL).

“And it transcended into a game situation. If somebody got beat, that was your brother who just got beat — and you covered for him, even if it wasn’t your job. It was almost instinctive.”

Rick Yallery-Arthur

Country: Trinidad & Tobago

Position: Defender

Years: ’68, ’69, ’70, ’71

Consistently charged with man-marking the opponent’s best attacker, Winston “Rick” Yallery-Arthur was a trusted defender who read the game well. Also known for his toughness, Yallery-Arthur finished the 1971 championship final against Saint Louis University playing with a partially separated shoulder.

Rick Yallery-Arthur

A teacher in his native Trinidad & Tobago prior to coming to America, Yallery-Arthur had intended to return home to the classroom after completing his studies at Howard University. But when he told his former employer in Trinidad that he’d earned an undergraduate degree, they told him that “a bachelor’s degree in America meant nothing.”

So it was on to Plan B for the former stalwart defender, and Yallery-Arthur enrolled in grad school at Howard to study History and Political Science. Turns out, it wasn’t a bad plan — sticking around “the Mecca” also afforded him the good fortune to stay close to his old Bison teammates as a writer and columnist for the Hilltop, Howard’s student newspaper.

Yallery-Arthur attacked his role as a columnist the same way he did as a defender. In the Nov. 10, 1972 issue of the publication, he called out his former team — including star goal-scorer Alvin Henderson — for not finishing early chances in a game against an overmatched Jacksonville University. “With this kind of start against a team that was not in their class, the Booters were expected to score against Jacksonville almost at will,” he wrote.

In that game, the Bison led 3-0 at the half — with goals from Richard Davey, Mori Diane, and Frank “Scrap Iron” Oshin. Howard’s second-half ball dominance was hardly reflected in the final score.

At least Henderson, who “muffed two early chances at point-blank range,” Yallery-Arthur wrote, would later redeem himself by getting the game’s last goal to give the Bison the easy 4-0 win.

Yallery-Arthur parlayed his straight-shooter approach into a long career in law — practicing in D.C., Maryland and the Caribbean — and covering everything from Bankruptcy to Civil Rights to Wills & Trusts.

Leslie Douglas-Jones

Country: Saint Kitts and Nevis

Position: Forward

Years: ’68, ’69, ’70

Ask Coach Lincoln Phillips today what qualities he looks for in a player, and he’s likely to tell you that all his players were quick and can dribble — regardless of position. Leslie Douglas-Jones, a right winger, fit Phillips’ model to a T.

Leslie Douglas-Jones

A steady and quick player, Douglas-Jones played for both Ted Chambers and his eventual successor, Phillips. Known for his reliable play, he also wasn’t bashful to take his goal-scoring chances on a team blessed with goal-scorers.

In the second game of the 1970 season, Howard manhandled Warren Wilson College 8-0 to up their goals tally to 12 in just two games. Douglas-Jones was one of four players to get a brace (Alvin Henderson, Keith Aqui and fellow defender Desmond Alfred were the others) that day.

Kenny Thomas

Country: Trinidad & Tobago

Position: Defender

Years: ’68, ’69, ’70

The origin of the long throw-in can unofficially be traced back to an international match between England and Scotland in 1882, according the18.com soccer writer Liam Hanley. And while there is little data on the origins of the long throw as a tactic in college soccer, few would argue that Kenny Thomas was anything less than a master at legally heaving a ball from the touchline.

Kenny Thomas

Called “Man Mountain” by his teammates (he was 6-foot-4, 230 pounds), Thomas was a long-throw specialist and a rugged left back. In the second game of the 1970 season — an 8-0 drubbing of Warren Wilson College — Thomas was credited with an assist, off a throw-in to Keith Aqui, who smacked a screamer from 40 yards out, his first of two goals that day.

After leaving Howard, Thomas coached youth soccer in Trinidad for several years, leading the St. Augustine Green Machine to several Secondary Schools Football League (SSFL) titles in the ’90s while also serving as an assistant with Tobago United, a Pro League team.

Former Howard teammate Alvin Henderson remembers Thomas, who passed away in December of 2015, fondly: “He was a gentle giant off the field and a true enforcer on it when needed,” Henderson said. “He always had our backs.”

Keith Aqui

Country: Trinidad & Tobago

Position: Forward

Years: ’70, ’71, ’72

A walk-on in 1970, Aqui – known as “Bronco” for his speed – was the outstanding player that year, leading Howard in goals with 25 (to match his age), which earned him a second-team All-American nod (he was first-team in ’71). Aqui formed an immediate and lethal partnership with Alvin Henderson, a duo that combined to score 91 goals over three seasons.

Keith Aqui

Prior to coming to America, Aqui attended Mausica Teachers College in Trinidad from 1965 to 1967.

The fact that Aqui was a relative unknown – and in his mid-20s – contributed to the NCAA’s inquiry of Howard University, many former teammates maintain. (Aqui graced the cover of the national soccer magazine of the day, Official Collegiate Scholastic Soccer Guide, in 1972, holding Howard’s ’71 championship trophy.)

The ’72 season would be Aqui’s last at Howard, and in February of ’73, the Dallas Tornado selected him in the first round (sixth overall) of the North American Soccer League draft. The Tornado released him in the preseason, and he joined the Baltimore Bays of the American Soccer League. In 1974, Aqui signed with the Baltimore Comets of NASL.

But it was at Howard where Aqui made his greatest mark before embarking on a long career as an attorney with the U.S. Department of Treasury.

Wrote soccer journalist Paul Gardner in 2016, shortly after Aqui passed away: “I remember Aqui quite well. I never spoke to him, but he spoke to me.”

Aqui’s legacy lives on in the form of Project YES Africa, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit he co-founded in 2015 that built a school in Khayelitsha, a township in Western Cape, South Africa that completed construction in 2023.

“A lot of this was done in Keith’s memory,” Aqui’s widow Antoinette Charles-Aqui said. “Keith always said, ‘If you start something, you need to finish it.’ ”

Spoken like the finisher he was.

Desmond Alfred

Country: Trinidad & Tobago

Position: Defender

Years: ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72

The team’s designated penalty shot taker was adept at reading the game and capable of playing multiple defensive positions for Coach Lincoln Phillips. A composed defender, Desmond Alfred was comfortable enough on the ball to play out of the back, which is a common trait for players in the modern era.

Desmond Alfred

Alfred was a school teacher in Tobago, and when he pondered his future, he didn’t want to end up a school principal down the road, like the crowded pack. That, to Alfred, couldn’t be his ceiling. So, he decided he’d to go America, having saved $250, enough to pay his first-semester school fees.

Alfred remembers it was a Sunday in August of 1969 when he left Port of Spain in Trinidad, arriving at JFK airport around 8 pm. After clearing immigration and customs, he jumped into a waiting Yellow cab bound for Grand Central Station to catch a bus to D.C. His driver — a white man — loaded his suitcases, and they pulled off. After a few minutes, the driver picked up another passenger and then told Alfred, rather forcibly, to hand over all his money.

Though shell-shocked, Alfred cooly handed over the money that took him two years to save. “I wasn’t about to get killed,” he said.

Eventually, Alfred got to D.C., thanks to a Good Samaritan giving him $40 for his bus fare. Upon arriving in the nation’s Capital, it was Ted Chambers — after hearing Alfred’s ordeal — who gifted the young Tobagonian not only the $250 he’d lost, but a full scholarship to Howard.

“In less than 24 hours, I had gone from losing all of my school fees for one semester to getting a four-year scholarship to play soccer. So, it’s not all bad. Those are the things that give me inspiration and hope,” Alfred said.

Football, for Alfred, was the easy part. He soon became one of the anchors in defense as well as the team’s designated penalty shot taker, and he was adept at reading the game and capable of playing multiple defensive positions. He was also comfortable enough on the ball to play out of the back.

Among his memories of that epic championship in ’71, Alfred said — footballer to footballer — there were no issues between Howard and Saint Louis. It was all about competing. He understands why Saint Louis’ coach Harry Keough never claimed the trophy after the championship was vacated.

“Keough … never uplifted that trophy,” Alfred said. “Why? Because he knows he lost the game. And that’s a footballer.”

Carlton Fraser

Country: Jamaica

Position: Forward

Years: ’68, ’69, ’70

Lifelong friend, fellow Jamaican soccer star Allan ‘Skill’ Cole, remembers Carlton Fraser as a humanitarian, telling The Gleaner in a 2021 interview: “I’ve seen patients come to him without money, and he fixes them up, writes a prescription and then goes into his own pocket and gives them money. He was a rare human being who gave it all to the people and asked for nothing.”

Carlton Fraser

Born in Kingston, Jamaica, where he attended Wolmer’s Boys School, Fraser studied medicine. As a member of the Bison team, Fraser was a specialist as well – a left-footed dribbler known for his crosses.

He returned to Jamaica in the mid-1970s where he would meet reggae superstar Bob Marley through his connection to Cole (Fraser’s schoolmate from the 1960s), who was a key member of Marley’s inner circle.

Fraser became a personal doctor to Marley and other Jamaican entertainers, including Marcia Griffiths, Tarrus Riley, Dean Fraser and the late Dennis Brown.

A Rastafarian, Fraser was at one stage the team physician for Jamaica’s soccer team, the Reggae Boyz. He passed away in November 2021, at age 74.

“Yuh can’t find a nicer person,” Cole said. “‘Pee Wee’ was a man that gave everything to people. A really, really great youth.”

Ronald “Sandy” Daly

Country: Guyana

Position: Midfielder

Years: ’69, ’70, ’71

A physical and rugged defender who would stick to a task, Daly was a dependable man-marker with good physical attributes who was also a key enforcer on the field. As president of Howard University’s Student Association (HUSA), a vehicle for progress and change on campus, Daly was a vocal and unapologetic change agent.

Ronald “Sandy” Daly

Responding to a poll question in the Dec. 3, 1971 edition of The Hilltop that asked students to share their thoughts on the Howard University student government’s greatest accomplishment, failure or mistake for the semester, Daly didn’t mince words:

“The ability to have survived in light of the farce that the students have made HUSA into. HUSA’s leadership has tried to appeal to the senses of supposedly mature, college-educated Black people, something meaningless in itself. Another important aspect is the inadequateness of the structure of HUSA.”

That’s who Daly was — a straight shooter, remembers former teammate Alvin Henderson.

“Sandy was not what I would describe as a footballer — certainly he could play football, but that wasn’t his whole character on campus,” Henderson explains. “Compared to guys like me, Ian [Bain] and Keith [Aqui], we were soccer players and the game was an integral part of our being. Sandy, on the other hand, was a student organizer who was focused on getting the best of us — foreign and domestic — to come together. And he did that.”

Charlie Pyne

Country: Nigeria

Position: Midfielder

Years: ’71-’77

If the Bison played with a rhythm that rocked the collegiate soccer landscape, it was Pyne who provided the beats. The Nigerian — who always had a boombox blasting the music of the time — played with a flair and style that complemented his fashion sense. “I was a very social animal … I couldn’t help it,” Pyne said. “I just like to entertain people and [make] everybody comfortable wherever I am.”

Charlie Pyne

Known for his quickness and ability to shoot powerfully with both feet, Pyne described the ’71 group as “an ideal team.”

“We could see from the beginning that we were onto something special, even though we couldn’t pinpoint what it was,” explained Pyne, who graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Economics in 1975 and a master’s degree in City and Regional Planning in 1977. “But you could feel that there was something special about it, [and] I realized that, as an individual, I brought something unique to that team.”

Pyne was candid when he was interviewed for The Bison Project, adding that he and Coach Lincoln Phillips had a strained relationship. “There was this jealously that emanated out of nowhere,” Pyne explained. “I recall the first time he saw me on the soccer field, he called me ‘Pele’ and ‘Crowd Pleaser.’ And I recall saying to him, ‘Where I come from, you please the crowd by showing your stuff.’ ”

Pyne takes great pride in knowing how his teammates regarded him, on and off the pitch. “I was a very social animal … I couldn’t help it,” Pyne said. “I just like to entertain people and [make] everybody comfortable wherever I am, regardless of the situation, you know?”

Andy Terrell

Country: USA

Position: Goalkeeper

Years: ’71-’77

“Did you know that there is a foreigner on Howard’s soccer team?” That was the opening paragraph in Lena Williams’ profile on Andy Terrell in the Nov. 19, 1971 edition of The Hilltop, Howard’s student newspaper. Recruited by Ted Chambers, Terrell was the lone African American on a team of immigrants, in ’71.

Andy Terrell

Even though Terrell — a Glen Mills, Pennsylvania native — had the ball skills to play in the midfield, at 6-3 and 175 pounds (with good hands), he was put in goal by Coach Lincoln Phillips to fight for minutes behind mainstays Amdemichael Selassie and Samuel Tetteh.

And while significant game minutes were hard to come by, Terrell found his place after feeling a bit like an outsider, at first. Ultimately, Terrell — who studied Electronic Engineering and Computer Science — was happy he chose Howard over Swarthmore College, Springfield College, and West Chester University.

Since graduating in 1977 — with a degree in Business Management — Terrell had lost touch with his former teammates. When told about The Bison Project, Terrell admitted to being oblivious to an asterisk even being attached to their ’71 championship. “I thought we had won it fair and square,” he said.

“If there’s an asterisk, it should go away.”

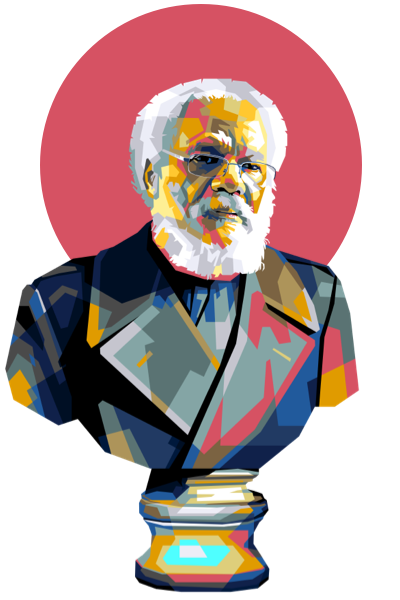

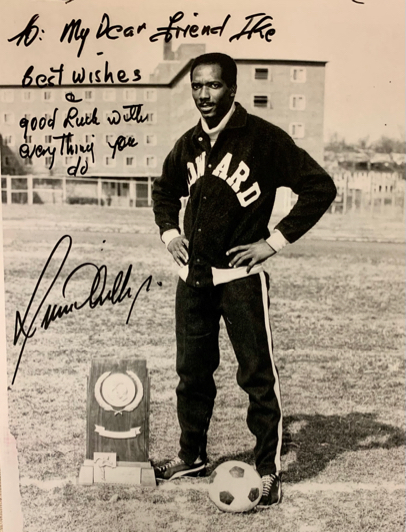

Lincoln Phillips

Country: Trinidad & Tobago

Position: Coach

Years: ’70-’80

Phillips met Ted Chambers, who started Howard’s soccer program, at an inner-city soccer clinic in Washington, D.C. Chambers observed Phillips mesmerizing the kids with moves they’d never seen before and approached him about joining Howard’s fledgling soccer program as an assistant. Phillips’ tenure as head coach would have a storied run from 1970 to 1980.

Lincoln Phillips

Phillips hadn’t been in the States long, but he’d already cemented himself a legend as goalkeeper for Trinidad & Tobago’s national team. When Chambers approached him about joining Howard’s fledgling soccer program as an assistant, it was the opportunity of a lifetime for the young “Tiger,” who at the time was a player/coach for the American Soccer League’s Washington Darts. Starting out as an assistant under Chambers’ tutelage would allow him to learn the coaching ropes and be the catalyst to the program’s growth.

When Phillips finally got the head coaching job, his high-pressure, uptempo style was a good complement to his no-nonsense coaching demeanor. Phillips’ practices were so tough, he was known around college soccer circles — and certainly among his players — as “Killer.”

“We call him Killer because every time we take the field we know he’s gonna kill us,” noted Keith Aqui in a 1972 Washington Post article.

From 1970 to 1980, Phillips made a name for himself, amassing an impressive 117-19-11 overall record, eight NCAA tournament appearances, and two national championships.

Phillips still believes HBCUs can make an impact on the American soccer landscape. “If we are to really move to the next level and develop our own Messi and Ronaldo, we have to get back to making the sport a priority, developing the game at the youth level and reopening the lines of communication with Caribbean and African players,” he said. “It’s time for us to be proud again and point to successful soccer programs on both the men’s and women’s side at HBCUs.”

And regarding the imprint his Howard teams of the early 70s had on college soccer, Phillips told the New York Times in a 2013 article that the impact is undeniable.

“Though it is hard to imagine when looking at today’s game in Europe, Black players from Africa and the Caribbean were never considered good enough to play in Europe in the ’60s through the ’80s,” he said. “In many ways, North America — through the NASL and college soccer — provided a haven for talented Black players from Africa and the Caribbean. So, I believe Howard had a role on the impact Black footballers had on the game in this country.”

Grant Wahl

Country: USA

Position: Soccer Journalist

Years: ’96-2022

Grant Wahl‘s first Sports Illustrated article appeared in the Feb. 24, 1997 issue, which featured a young Derek Jeter and Alex Rodriguez, on the cover. Wahl’s story wasn’t about two of Major League Baseball’s biggest rising stars, however; it was about Howard University’s 1974 national championship team — a story he’d been enamored with for years.

Grant Wahl

Wahl worked at Sports Illustrated for 24 years, landing his dream job at the iconic magazine in November of 1996 as a fact-checker, straight out of college.

“I got a subscription to Sports Illustrated as a Christmas present from my parents when I was 10 and that became my bible,” Wahl recalled in a 2015 interview. “I remember telling my friends in high school that I wanted to write for Sports Illustrated someday.”

So when Wahl had the opportunity to earn his first byline, he knew that the story of Howard University’s 1974 soccer team was the one to tell.

The longtime soccer fan met up with Ian Bain and his wife Betty in their northern Virginia home; he also spent quality time with Lincoln Phillips in his home in Columbia, Md., looking through old magazine articles and plagues, unearthing a story that had been all but forgotten for decades.

When looking for subject matter experts — during the filming of the ESPN documentary “Redemption Song” — producer Mark W. Wright’s first call was to Wahl, who originally learned of the story while in grad school at NYU, where he wrote a research paper for an African American Sports History class on the team.

“Grant just seemed to have an interest in social justice, which carried on until the very end with him,” explained Jeffrey Sammons, Wahl’s former professor in that class. “He had a big interest in soccer, and those two things came together, coalesced in Howard’s travails. I don’t think I was the one who directed him or put him in that direction. I think that he was self-directed.”

Wahl, who wrote more than 50 cover stories for Sports Illustrated, died of an aneurysm on Dec. 10, 2022, while covering the World Cup in Qatar. He was 48 years old. He was well aware of The Bison Project and was a massive supporter of the initiative.

Said Wright: “Grant was at the very top of my list of people who I most wanted to hear this podcast. He’s very much a part of this story, and it saddens me that he’s no longer with us.”

Paul Gardner

Country: USA

Position: Soccer Journalist

Years: ’65-Present

Paul Gardner vividly remembers being in that crowded ballroom at the McAllister Hotel in Miami for the NCAA’s final four banquet, when Lincoln Phillips — in no uncertain terms — called out the NCAA. “I was at the dinner when he made that very fine speech — calm, relaxed but full of anger,” recalls Gardner, who was among a small contingent of journalists covering the 1972 soccer postseason.

Paul Gardner

Of course, Phillips was hot under the collar because the sting of losing a semifinals match to Howard’s nemesis St. Louis University the night before still burned — dashing any hopes of the school repeating as national champions.

With a captive audience of some of the nation’s top college soccer coaches and NCAA officials, he spit fire. “You could just feel it,” Gardner continued. “You could just see him calling it back to tell you, in measured tones, that what you saw [against St. Louis] was not Howard but the ‘remnants of Howard’ after the NCAA had gone at them,” Gardner said, lowering his tone to sound like Phillips.

A longtime critic of the NCAA, Gardner doesn’t pull punches when the topic is college soccer in the early ’70s, which he said mostly consisted of leadership that knew nothing about the game and featured a playing style that resembled American football without shoulder pads.

“The only time that I remember [fondly] watching college soccer of the early ’70s was — suddenly, out of the blue — Howard University, who were playing much closer to what I thought soccer should be,” explained Gardner, who has covered the sport since the mid-1960s, writing for the likes of Sports Illustrated, The New York Times, and The Guardian, among other publications.

“And presiding over all that was Lincoln Phillips, who was certainly a soccer man whereas a lot of the college soccer people were not soccer people at all,” explained Gardner, a 2010 recipient of the Colin Jose Media Award from the National Soccer Hall of Fame.

In a conversation with Mark W. Wright in December 2022, the 92-year-old Englishman hinted at some optimism for the NCAA and Howard: “The trends and the attitudes and the positions of people are very different now from what they were 40, 50 years ago,” he said. “And I think there is a much more widespread feeling that injustices were done, and people want to correct them.”

About the BISON Project

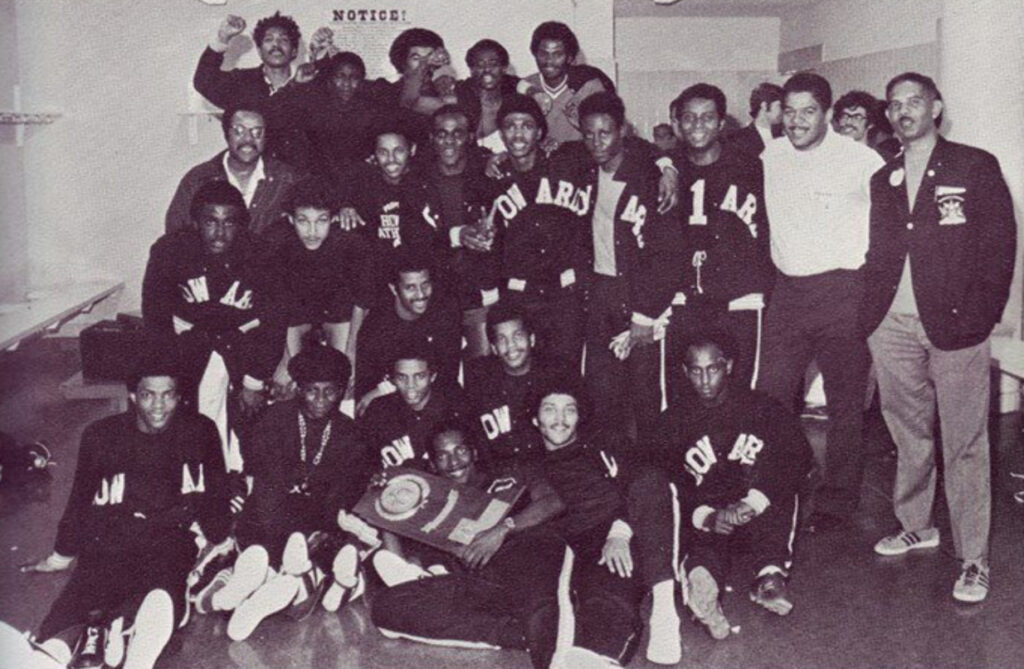

On Dec. 30, 1971, Howard University made history – defeating soccer powerhouse Saint Louis University to win a national championship. It was the first-ever national championship – in any sport – for the prestigious historically Black college and university (HBCU).

Exactly one year later, the NCAA would strip Howard of its title – banning the team, which included several immigrant players, from postseason play for the 1973 season and placing the program on probation for one year. (The team’s semifinal finish in 1970 was also wiped from the NCAA’s record books.)

The NCAA charged that two players from Howard’s starting 11 in ’71 were ineligible because of playing amateur soccer in Trinidad and Tobago, while two others were academically ineligible. Howard argued that the players in question were all in good academic standing, with GPAs over 3.0, and that the NCAA’s rules on amateurism discriminated against foreign student-athletes.

While Howard would win another national championship in 1974, the school – despite claiming its innocence – never got the 1971 title back. To this day, the title is still unclaimed. Saint Louis University, the team Howard beat, refused to accept the trophy by default.

More than 50 years later, the sting of being branded as cheats still burns for the players – and the former students – who all believe the Bison won that title fair and square.

This three-episode podcast series gives the players the opportunity to speak their truth, and start a movement to remove the asterisk and return the 1971 national championship to its rightful owner.

From Meadowlark and Campside Media, this is Sports Explains the World, a collection of podcasts that use sports-related stories to reveal greater truths about the world and society. The Bison Project, one of a handful of multi-episode stories in the series, was reported and written by Mark W. Wright, produced by Janae Morris and Cody Nelson, and narrated by Sam Dingman.

Mark W. Wright

The Bison Project was written and reported by sports journalist and filmmaker, Mark W. Wright, a Howard alum, who has tracked this story for close to a decade. Wright was a producer on ESPN’s Redemption Song 30 for 30 documentary that aired in 2016 and spotlighted the story of Howard’s soccer team in the 1970s. But Wright always felt that the 16-minute film only scratched the surface. Said Wright: “The Bison Project is our opportunity to get this story right — not only for the sake of storytelling, but for the players who never had a chance to speak of their experiences.”

Mark W. Wright

Bringing The Bison Project to life has been a nearly 10-year endeavor for Mark Wright. A sports journalist and filmmaker, Wright came across the story of Howard’s soccer dominance shortly after Coach Lincoln Phillips released his autobiography in 2014. Wright pitched the team’s story to ESPN Films, and it later became the 30 for 30 documentary Redemption Song.

But the Howard alum knew that the short film only scratched the surface — and there was more to say about the 1970 season, which is where the story really begins.

“The Bison Project is our opportunity to get this right. I made a promise to the players back in 2016 that we’d properly tell their story,” explained Wright, whose inspiration for wanting to seek justice for these true champions is his former high school soccer coach, Ian Bain, a freshman on that ’71 team.

GALLERY

The HARDER THEY COME

The Bison arrived in Jamaica after their championship, greeted by Michael Manley, who became the country’s fourth Prime Minister in 1972.

The Harder They Come

Days after capturing the school’s first national championship, the Howard Bison declined President Nixon’s White House invitation and instead embarked on a victory-lap road trip to sunny Jamaica.

Lincoln Phillips’ squad got off to a hot start – on Jan. 4, 1972 – with an easy 4-0 win over the University of the West Indies, with two tallies from Ian Bain.

Three days later – on Jan. 7 — the Bison faced Boys’ Town Invitational XI in front of 3,000 fans at Jamaica’s National Stadium and hardly disappointed – winning 7-0 (including braces from Alvin Henderson and Keith Aqui, and tallies from Donnie Simmons, Mori Diane and Tony Martin).

The following day – on Jan. 8 – Phillips’ boys faced a rested Jamaica All-Schools team and showed tired legs, conceding a 2-1 loss, with Anthony Martin’s free-kick tally the sole bright spot.

The squad’s last game on Jan. 10 was against the Jamaica Olympic team, and it hardly yielded the result Phillips had hoped. The Bison suffered yet another defeat, losing 2-0, in front of more than 5,000 onlookers at the National Stadium.

What should have been a full-on celebration soon turned into a full-on nightmare for Howard, as rumors had already started to swirl that the NCAA was on their heels for alleged infractions.

Mr. Big Stuff

Coach Lincoln Phillips, already a legendary goalkeeper in Trinidad & Tobago, was respected — and feared — by his players.

Ain’t no stoppin’ us now

With a strong incoming recruiting class, the Bison collectively believed more titles would come after ’71.

Ain’t no stoppin’ us now

It’s a Family Affair

Sly and the Family Stone’s No. 1 hit was the team’s anthem, and the feeling was deep in the moments after capturing the national championship in 1971.

It’s a Family Affair

Soul Rebel

Washington, D.C., native and budding journalist Lena Williams was a freshman in 1968, a year when Howard students demanded more of the university’s administration.